How to Write a Literature Review for a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide for Real Researchers

Let’s be honest: sitting down to figure out how to write a literature review for a research paper often feels like trying to map a forest while you’re standing in the middle of a thicket. You have a mountain of PDFs, dozens of browser tabs open, and that nagging feeling that you’ve missed the one “perfect” paper that would tie everything together.

It’s the part of the research process that keeps most students and early-career academics up at night. Why? Because a literature review isn’t just a summary of what others have said. It’s a synthesis. It’s a conversation. It’s the foundation upon which your entire study stands.

If you’ve been feeling overwhelmed, you’re in the right place. We’re going to strip away the academic jargon and look at how to build a review that actually adds value to your field and helps you finish your paper without losing your mind.

What Is a Literature Review, Really?

Before we get into the “how,” we need to kill a common myth. A literature review is not an annotated bibliography.

If your draft looks like a list “Smith (2020) said X. Jones (2021) said Y. Brown (2022) said Z” you aren’t writing a review. You’re writing a grocery list of academic names.

A true literature review is a critical evaluation of the existing body of knowledge. It’s where you show your reader that you’ve done your homework, you understand the “state of the art,” and you’ve identified a specific gap that your research is going to fill.

Think of it like being the host of a dinner party. You’ve invited all the top experts in your field. Your job isn’t just to let them talk individually; it’s to facilitate a conversation between them. You point out where they agree, where they’re practically shouting at each other, and where they’ve all ignored a crucial detail.

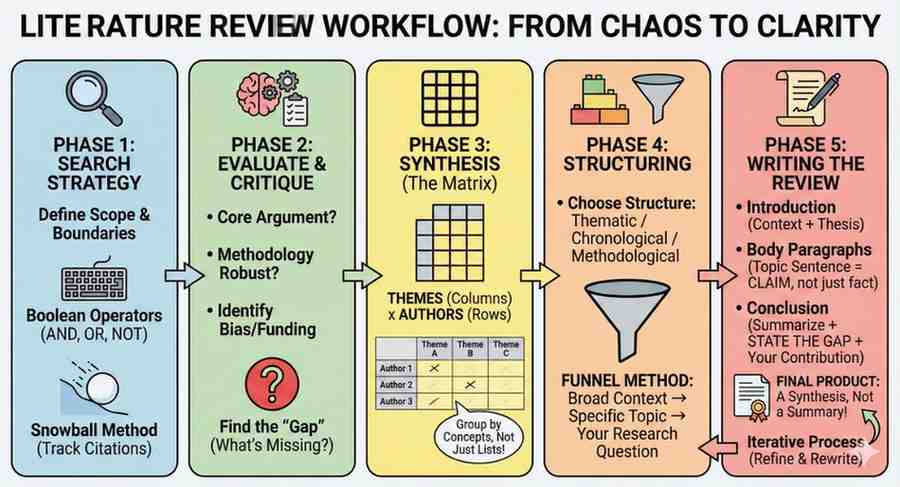

Phase 1: The Search Strategy (Don't Drown in PDFs)

The biggest mistake researchers make is searching without a filter. You can’t read everything. If you try, you’ll never start writing.

1. Define Your Scope

What are the boundaries of your research? If you’re writing about remote work productivity, are you looking at the last five years or the last twenty? Are you focusing on psychological impacts or economic ones?

Narrowing your scope early prevents you from getting distracted by “interesting but irrelevant” tangents.

2. Use Boolean Operators Like a Pro

Don’t just type a sentence into Google Scholar. Use Boolean operators to refine your results:

AND: (Remote Work AND Productivity) – finds papers containing both.

OR: (Remote Work OR Telecommuting) – finds papers containing either.

NOT: (Remote Work NOT Freelancing) – excludes specific terms.

3. The “Snowball” Method

Once you find three or four “seminal” papers (the ones everyone seems to cite), look at their reference lists. Then, use a tool like Connected Papers or Google Scholar’s “Cited by” feature to see who has cited them since they were published. This helps you trace the evolution of an idea through time.

Phase 2: Evaluating and Critiquing Your Sources

Not every peer-reviewed paper is a “good” paper. As a researcher, you are expected to be a skeptic. Just because something is published doesn’t mean it’s the final word on the subject.

Ask yourself these questions as you read:

- What is the core argument? Can you summarize it in two sentences?

- What methodology did they use? Is it robust, or are there obvious flaws in how they collected data?

- Is there a bias? Who funded the research? Is the author pushing a specific agenda?

- What did they miss? This is the most important question. This is where your “gap” lives.

Phase 3: The Secret Sauce – Synthesis

This is the stage where most people get stuck. How do you move from “summarizing” to “synthesizing”?

The answer is the Synthesis Matrix.

Instead of organizing your notes by author, organize them by theme. Create a table where the columns are the major themes or variables you’re investigating, and the rows are the authors.

Example Synthesis Matrix

Author (Year) | Theme A: Mental Health | Theme B: Technology Barriers | Theme C: Managerial Trust |

Smith (2022) | Found high burnout rates | N/A | Argues trust is declining |

Chen (2023) | Focuses on work-life balance | Highlights VPN issues | Suggests trust is high |

Davis (2021) | N/A | Hardware limitations | Link between trust & output |

When you look at your research this way, the paragraphs almost write themselves. Instead of talking about Smith, you talk about the “Conflicting Views on Managerial Trust,” citing Smith, Chen, and Davis together.

How to Structure Your Literature Review

Structure is the “skeleton” that keeps your paper from collapsing. While there’s no single “correct” way to do it, most successful reviews follow one of these three patterns:

- The Thematic Approach (Most Common)

You organize your review around different topics or issues. If you’re researching climate change policy, you might have sections on “Carbon Taxing,” “Renewable Subsidies,” and “International Treaties.”

- The Chronological Approach

This works best if you’re tracing the evolution of a theory or a historical event. You show how the thinking changed from the 1970s to the present day. However, be careful not to just list events; you still need to analyze why the shifts occurred.

- The Methodological Approach

If your research is focused on how things are studied, you might group sources by their research methods (e.g., qualitative studies vs. quantitative studies).

Expert Tip: Regardless of the structure, always use the “Funnel Method.” Start broad (the general field), get narrower (specific sub-fields), and end at the point of your research question.

Writing the Review: A Human-Centric Approach

Now we get to the actual writing. This is where you need to sound like a confident scholar, not a student trying to hit a word count.

The Introduction

Your intro needs to do three things:

- Define the topic and provide context.

- Explain why this topic matters (the “So what?” factor).

- State your thesis or the organizational structure of the review.

The Body Paragraphs

Every paragraph should start with a strong topic sentence that makes a claim.

- Bad: “Wilson (2019) conducted a study on sleep deprivation.” (This is a fact, not a claim).

- Good: “While early research focused on the physical effects of sleep deprivation, recent studies have shifted toward cognitive impairment.” (This is a claim that synthesizes multiple papers).

The Conclusion

The conclusion is often the most neglected part. Don’t just summarize what you just said. You need to:

- Summarize the major findings of the literature.

- Explicitly state the gap. “Despite the wealth of research on X, there remains a significant lack of data regarding Y.”

- Explain how your research paper will address this gap.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even the smartest researchers fall into these traps. Here’s how to stay clear of them:

- The “Everything and the Kitchen Sink” Trap: You don’t need to cite every paper you read. If a source doesn’t directly contribute to the “story” of your research, cut it.

- Relying on Secondary Sources: If Smith (2022) cites Jones (1995), don’t just cite Smith. Go find the original Jones paper. Misinterpretations happen, and you don’t want to inherit someone else’s mistake.

- Passive Voice Overload: While academic writing is often formal, overusing the passive voice makes your writing sluggish. “It was found by researchers…” is weaker than “Researchers found…”

- Lack of Voice: Don’t let the citations drown you out. It’s your paper. The citations are there to support your argument.

Myths vs. Facts

Myth | Fact |

More citations = a better review. | Quality and relevance matter more than quantity. |

You should only use recent papers. | Seminal, older works provide the necessary foundation. |

The literature review is written first. | Most researchers write (and rewrite) it throughout the entire process. |

You must agree with the experts. | Identifying flaws in “expert” work is the hallmark of a great researcher. |

Tools to Make Your Life Easier

You don’t have to do this with a pen and a legal pad. Modern research tools are game-changers:

- Zotero / Mendeley: These are non-negotiable. They manage your citations and allow you to insert them into Word or Google Docs with a single click.

- Notion: Great for creating a “Research Hub” and keeping your synthesis matrix organized.

- ResearchRabbit: Think of it like Spotify for research papers. It suggests related papers based on your “collections.”

- Otter.ai: If you think better by talking, record yourself explaining a concept and then transcribe it. It’s often easier to edit a “brain dump” than to stare at a blank screen.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- How long should a literature review be?

For a standard journal article, it’s usually 15–25% of the total paper. For a dissertation, it can be an entire chapter (30–50 pages). Always check your specific department’s guidelines.

- Can I use “I” in a literature review?

This depends on your field. In the humanities and some social sciences, “I” is increasingly accepted. In the hard sciences, it’s still generally discouraged. When in doubt, stick to the third person or check the “Instructions for Authors” of your target journal.

- How many sources do I need?

There is no “magic number.” However, for a graduate-level paper, 20–40 sources is a common range. For a PhD thesis, it’s often 100+.

- What if there is no literature on my topic?

Unless you’re researching something truly alien, there is always literature. You might need to look at “parent” topics or “analogous” fields. If you’re studying a brand-new software, look at the literature on the adoption of similar technologies.

Final Thoughts on Mastering the Review

At the end of the day, learning how to write a literature review for a research paper is about developing a specific type of vision. You’re learning to see the connections between disparate ideas. You’re learning to see the “shape” of human knowledge and, more importantly, where the edges of that knowledge are fraying.

Don’t aim for perfection in your first draft. Write the “messy” version where you just try to get the ideas down. The clarity comes in the editing. By the time you finish, you shouldn’t just be an expert on what has been done you should be the most qualified person to explain what needs to happen next.

Writing a literature review is a marathon, not a sprint. Take it one theme at a time, stay organized, and remember: you aren’t just reporting on the conversation you’re joining it.

If you want to understand how AI tools can help you in writing literature review, you will love these courses that are meant for researchers like you : https://thephdcoaches.com/courses/.

About Dr. Tripti Chopra

Dr. Chopra is the founder and editor of thephdcoaches.blogs and Thephdcoaches Learn more about her here and connect with her on Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.

Our Featured Courses

Explore Our Courses

Empowering Scholars and Academics to Achieve Excellence Through Personalized Support and Innovative Resources

Our Featured E-Products

Explore Our Products

Empowering researchers with expert tools and personalized resources to achieve academic success.

Leave a Reply