The Art of the Deep Dive: How to Write a Literature Review That Actually Matters

Writing a literature review often feels like being dropped into the middle of a massive, crowded cocktail party where everyone has been talking for decades. Your job isn’t just to stand in the corner and eavesdrop. You have to understand the themes of the conversation, identify who’s arguing with whom, and eventually, find the right moment to contribute your own voice.

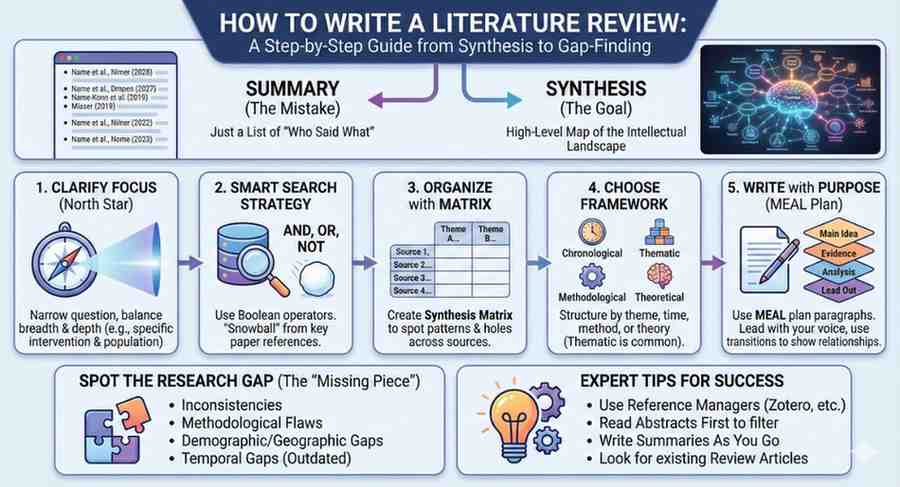

Learning how to write a literature review is a rite of passage for researchers, but it’s also a skill that separates “good” papers from “groundbreaking” ones. It’s not a book report or a chronological list of “who said what.” It’s a synthesis—a high-level map of the intellectual landscape.

Whether you’re tackling a dissertation chapter or a standalone review article, the goal is the same: to show that you’ve done the work, understood the nuances, and identified a gap that your own work intends to fill.

What Exactly Is a Literature Review (and What Isn’t)?

Before we get into the mechanics, let’s clear the air. A literature review is a critical analysis of existing research on a specific topic.

It is not a summary. If your paragraphs all start with “Smith (2019) said…” and “Jones (2020) found…”, you aren’t writing a review; you’re writing a list. A true review looks for patterns, conflicts, and evolutions in thought.

Think of it this way:

A Summary: Tells the reader what happened in one study.

A Synthesis: Tells the reader how five different studies collectively changed the way we think about a problem.

Why does it matter?

You aren’t just doing this to satisfy a rubric. A well-executed review provides the “why” behind your research. It justifies your project’s existence by proving that there is something we don’t know yet—or something we’ve been looking at the wrong way.

Step 1: Clarifying Your Focus (The "North Star")

The biggest mistake I see? Trying to boil the ocean. If your topic is “Mental Health in Schools,” you’ll be buried under 50,000 papers before lunch.

You need a narrow, focused research question. Instead of “Mental Health in Schools,” try “The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Anxiety Levels in Middle School Students (2015-2025).”

The “Breadth vs. Depth” Balance

You need enough breadth to show you know the field, but enough depth to be meaningful. Ask yourself:

- What are the core debates?

- What are the “landmark” studies everyone cites?

- Which methodologies are standard in this field?

Step 2: The Search Strategy (Beyond Google Scholar)

While Google Scholar is a great starting point, relying on it alone is like trying to learn about history by only reading the headlines. You need a systematic approach to finding sources.

Use Boolean Operators

Don’t just type words into a search bar. Use operators to refine your results:

- AND: (Mindfulness AND Anxiety) — narrows results.

- OR: (Mindfulness OR Meditation) — expands results.

- NOT: (Mindfulness NOT Clinical) — excludes irrelevant data.

The “Snowball” Method

Once you find a “gold mine” paper—one that is perfectly aligned with your topic—look at its reference list. Who did they cite? Then, look at who has cited that paper since it was published. This allows you to trace the genealogy of an idea backward and forward in time.

Step 3: Organizing the Chaos (The Synthesis Matrix)

By the time you have 30 or 40 papers, your brain will start to turn into mush. You’ll forget which author used which methodology or what the sample size was in that one study from 2018.

This is where a Synthesis Matrix becomes your best friend. It’s a simple table where the columns represent themes or variables, and the rows represent the sources.

Source | Theme 1: Digital Literacy | Theme 2: Socioeconomic Gap | Theme 3: Age Factors |

Smith (2021) | High correlation | Discussed heavily | Focus on Teens |

Nguyen (2022) | Found no link | Minimal mention | Focus on Adults |

Garcia (2023) | High correlation | Focus of study | All ages |

When you fill this out, you’ll suddenly see the “holes” in the research. If everyone is focusing on teens (Theme 3), but no one is looking at the socioeconomic gap (Theme 2) in that context, you’ve found your gap.

Step 4: Choosing Your Structural Framework

You can’t just throw all your notes into a Word doc and hope for the best. You need a narrative structure. There are four common ways to organize a literature review:

1. Chronological

This tracks the evolution of a topic over time. Use this if the history of the idea is central to your argument. For example, how the definition of “intelligence” has shifted from the 1950s to today.

2. Thematic

This is the most common and often the most effective approach. You organize by sub-topics or themes. This shows a high level of critical thinking because you’re grouping authors based on their ideas, not just their publication dates.

3. Methodological

Sometimes, the how is more important than the what. If you’re reviewing different ways to measure climate change, you might organize by “Qualitative Approaches,” “Quantitative Modeling,” and “Mixed Methods.”

4. Theoretical

If your work is heavy on philosophy or high-level theory, you might organize by different schools of thought (e.g., Feminist Theory vs. Post-Colonial Theory).

Step 5: Writing the Review (The "Meat")

Now, we get to the actual writing. This is where most people get stuck. The secret to a human-sounding, authoritative review is to use your own voice to lead the dance.

The Introduction

Establish the context. Why is this topic important right now? Define your scope. Tell the reader exactly what you will and won’t be covering.

The Body Paragraphs (The MEAL Plan)

A great way to ensure your paragraphs don’t become summaries is to follow the MEAL acronym:

- M – Main Idea: Start with a claim about the literature (e.g., “There is a significant disagreement regarding the efficacy of X.”)

- E – Evidence: Bring in the sources. (“Smith argues A, while Jones suggests B.”)

- A – Analysis: Explain the evidence. Why do they disagree? Is one study more rigorous than the other?

- L – Lead Out: Transition to the next point or link back to your overall thesis.

Using Transitions to Show Relationships

Don’t just use “furthermore” or “in addition.” Use transitions that show relationship:

- To show contradiction: “Conversely,” “Despite these findings,” “However, a more recent study suggests…”

- To show consensus: “A growing body of evidence indicates,” “Consistent with previous findings,” “Scholars broadly agree that…”

Common Pitfalls: How to Avoid the "Academic Robot" Trap

I’ve edited hundreds of reviews, and the same mistakes crop up every time. If you want your writing to feel professional yet accessible, watch out for these:

- The “Laundry List” Syndrome: If every sentence starts with a name and a date, you’re listing, not reviewing.

- Over-quoting: We want to hear your synthesis, not a string of other people’s quotes. Paraphrase as much as possible. Only quote if the original wording is so unique it can’t be changed.

- Ignoring the “Grey” Literature: Don’t just look at peer-reviewed journals. Sometimes government reports, white papers, or conference proceedings hold the most current data.

- Lack of Critique: A review isn’t just about what’s there; it’s about what’s wrong with what’s there. Don’t be afraid to point out small sample sizes, biased funding, or outdated methods.

Myths vs. Facts: The Literature Review Edition

Myth | Fact |

More sources always mean a better review. | Quality and relevance beat quantity every time. |

You should only include sources that agree with you. | Including dissenting opinions shows intellectual honesty and depth. |

A literature review is a static document. | It’s an iterative process. You’ll likely update it as you write your findings. |

You must read every paper from cover to cover. | Strategic reading (abstract, intro, conclusion) helps you filter what needs a deep dive. |

Expert Tips for a Painless Process

- Use Reference Management Software: If you aren’t using Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote, you’re making your life 10x harder. These tools format your citations instantly and keep your PDFs organized.

- Read the Abstract First: Don’t commit to a 30-page paper until you’ve read the abstract. If it’s not relevant, toss it.

- Write as You Go: Don’t wait until you’ve finished reading 50 papers to start writing. Write summaries and thematic notes while the ideas are fresh.

- Look for “Review Articles”: Someone might have already written a literature review on your topic three years ago. Use their bibliography as a starting point, then update it with the latest research.

How to Identify the "Gap"

The whole point of learning how to write a literature review is to find the “missing piece.” How do you do that? Look for:

- Inconsistencies: Why do two studies on the same topic have totally different results?

- Methodological Flaws: Has the topic only been studied quantitatively? Maybe it needs a qualitative perspective.

- Geographic/Demographic Gaps: Has this been studied in the US but never in Southeast Asia? Has it been studied in men but not women?

- Temporal Gaps: Is the “foundational” research 20 years old? Does it still apply in the age of AI and social media?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How many sources do I need for a literature review?

There’s no magic number. For a course paper, 10–15 might suffice. For a dissertation, you’re looking at 50–100+. The real answer is: enough to represent the “current conversation” fully.

Should I use the first person (“I”)?

This depends on your field. In the humanities and social sciences, “I” is becoming more common. In the hard sciences, “this review examines” is usually preferred. When in doubt, check your department’s style guide.

How old is “too old” for a source?

Generally, try to keep 70–80% of your sources within the last 5–10 years. However, “seminal” or “landmark” papers (the ones everyone cites) should always be included, regardless of their age.

What is the difference between a literature review and an annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a list of sources with a brief descriptive and evaluative paragraph for each. A literature review is a cohesive essay that synthesizes those sources into a narrative.

Conclusion: Putting it All Together

Mastering how to write a literature review is about moving from a consumer of information to a curator of ideas. It’s a challenging, often tedious process, but it’s the only way to ensure your own research stands on a solid foundation.

By focusing on synthesis rather than summary, and by organizing your thoughts around themes rather than dates, you create a document that doesn’t just “check a box.” Instead, you provide a roadmap for others in your field. You show exactly where the conversation has been—and exactly where you’re about to take it.

Now that you’ve got the framework down, it’s time to stop reading about writing and start actually writing. Grab your top five sources, fire up your synthesis matrix, and start looking for those patterns.

If you want to understand how AI tools can help you in writing literature review, you will love these courses that are meant for researchers like you : https://thephdcoaches.com/courses/.

About Dr. Tripti Chopra

Dr. Chopra is the founder and editor of thephdcoaches.blogs and Thephdcoaches Learn more about her here and connect with her on Instagram, Facebook and LinkedIn.

Our Featured Courses

Explore Our Courses

Empowering Scholars and Academics to Achieve Excellence Through Personalized Support and Innovative Resources

Our Featured E-Products

Explore Our Products

Empowering researchers with expert tools and personalized resources to achieve academic success.

Leave a Reply